NFTs… selling nothing for the stonks ($$$)

An insight into the mechanics and terminology behind the NFT phenomenon and a warning not to get involved without plenty of prior knowledge about the pitfalls – Part 1 of a personal view by Tiny Spark’s Anton McCoy.

The world of NFTs has been around for a while. However, due to some eye watering online and real-world NFT sales, this mysterious world has now been exposed to a wider population. Here, I’m going to explain what NFTs are, what exactly you are purchasing, how NFT marketplaces actually work – and talk about the ecological impact that keeping a record of NFT sales is having.

What is an NFT?

NFT stands for non-fungible token. Let’s take that phrase apart, starting with ‘fungible’. This is mainly an economic term, with ‘fungibility’ being the property of a good or commodity whose individual units are essentially interchangeable with and indistinguishable from another. The most common example is often considered to be a bank note, so if I gave a friend £10 one day and they gave me a £10 note back the next day, the fact this is a different physical bank note doesn’t matter. It’s the same with a DVD or a pair of socks and so on. You purchase of pair of red socks online and those red socks, as pictured, arrive. The warehouse holds thousands of these same socks, and you don’t care which pair you receive. They are fungible.

Non-fungible is therefore the opposite: something unique, such as a signed, original painting or a rare or limited-edition item like a special football player card. Finally, there’s the word‘token’, the most nebulous word in the phrase, which means in effect a record in a database, validated by ‘the blockchain’ (more on that later).

In the digital world, there isn’t really such a thing as non-fungible assets, or even limited-edition assets. A digital image can be copied and saved on to another device and the 0s and 1s that are stored on two different computers are digitally identical – and therefore fungible. The purpose of NFTs is to create artificial rarity and ‘non-fungibility’ for solely digital access by linking an asset to a row in a database, with that database then validated against the blockchain, making the relationship of that asset and a cryptocurrency wallet immutable from then on.

There are, in general, two approaches to NFTs: there are those stored within a specific website (validated against the blockchain) and those on the open marketplace (again validated by the blockchain). The first example is the way many companies might set up, whilst the marketplace is where an individual artist, for example, might try and sell their art.

Let’s look at these two approaches.

Creating your NFT-selling website

Say you want to get into the NFT business, or to make to additional money on digital assets you already have – for example, if you already produce games and have assets from those games. In both cases (if you don’t want to use a marketplace, for example OpenSea, like an eBay for NFTs), you will need to set up a database.

Existing digital assets

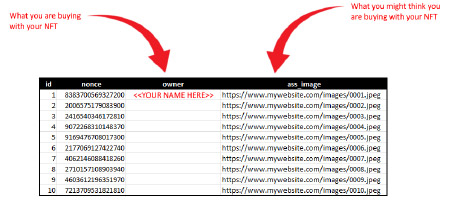

Let’s imagine you created 10,000 rows in this database (for some reason 10k items is currently a popular number of items to put up in an NFT sale). Simply offering a place in this database is going to be a hard sell, as this is all you’re selling. Therefore, to make this database placement more appealing, you associate each row with an image; an image that doesn’t appear in any of the other rows in your database. This means that since this database is now unique, and the image associated with this image is unique, this can be defined as non-fungible. A user then decides to purchase a row and the user is assigned a token. The token is put into the database, with the transaction recorded and verified in the blockchain.

At this point, you might be wondering what exactly the user has purchased. Is it the art, the rights to the art or the copyright to the art? No, it’s none of these things. The only thing the user has in fact purchased is a row in a database, and the fact that this row and its purchase has now been stored and verified in the blockchain. If you look at the blockchain ledger, the only reference to the image will typically be a URL to where the image is hosted. The user has no other rights to this image and, if the user printed a T-shirt with that image on it, could be infringing someone else’s copyright.

When you think about it, not owning any of the rights or the copyright makes perfect sense to the seller. After all, would money-focused organisations like the NBA or others happily give away rights to a specific sporting highlight to a ‘random person’, meaning they’d then have to pay you royalty fees if they used it themselves? Of course not.

For companies with loads of existing artworks, NFTs are a great way to make money from nothing, simply by selling a row in a database linked to something a fan might like, but without giving away in rights to the image itself – whilst the purchaser may feel like they own the linked association with their row in the database, even though they’re not always its unique owner even then, because companies can create multiple versions of the database, linking the same images to each row as before, whilst saying maybe that each database is per country; BIGCORPNFTUK, BIGCORPNFTFRANCE …etc. If each database is unique, then the purchase remains non-fungible.

Create your own assets

If you wanted to create a NFT library but you don’t have images to associate with a spot in a database, you can auto-generate them. If you take the typical 10,000 run approach we mentioned earlier, for example, all you’d have to do would be create facets for components of a default image and use a computer program to generate permutations. To create 10,000 different images, you might pick 4 areas of this starting template to ensure variation. have For example:

- 10 different types of headwear (hat, crown, bald …etc)

- 10 different facial expressions (smiling, angry, sad …etc)

- 10 different torsos (neon shirt, turtleneck & chain, dadbod …etc)

- 10 different backgrounds (white, yellow, rainbow …etc)

10*10*10*10 = 10,000, meaning you’d already have enough combinations to create an image to associate with each row in the database.

To mix things up a little, if this output was stored in a regular table or array, it might be too obvious that the images were generated, as each xxx8 item would be wearing the same headwear. You could simply sort the array randomly instead and output it as generated digital files called arraynumber.jpeg – eg 2434.jpeg or 0043.jpeg. This allows easy binding to the database, indicating which image is related to which row in the database. After all, as the seller, you don’t care which one goes where, only that they are all convincingly assigned in a unique way.

Are sites like these safe?

This is a tricky question, as the NFT world is still new. However, if are looking to purchase an NFT and research via a resource like YouTube, you’ll often see buying an NFT described as an INVESTMENT, whilst adding you should only purchase with money you are willing to lose. This is the same terminology used when it comes to gambling or putting money into to stock market. In other words – buyer beware!

Of course, this is also true to some degree with the physical art market, where value is as much perceived as tangible. Someone may have created a piece worth millions, but if that artist was then found to have committed some heinous crime, the value might drop to zero. If you’re purchasing something as an investment with no intrinsic value – ie something usable, where the cost is related to the amount of labour put in to produce it – it‘s either an investment that comes with risk, or something you personally like and therefore you don’t care too much about its value.

Company-owned NFT sites are completely unregulated currently and that inevitably means they are littered with scams, insider dealing, money laundering and other criminal issues. Scams are so rife within the NFT community that there is even a specific term for it: ‘rugging’ or being ‘rugged’. Not to say that they’re all bad – as long as buyers always confront the very real possibility of losing all their money.

One notable ‘rugging’ example to date is ‘Evil Ape’, which used the Ape design prior to a fighting game being launched – the most well-known NFTs sold so far. The classic 10,000 different images were generated, using the 10 variations of 4 elements methodology. The sellers had a website, a Twitter account and all the expected social channels. They held an auction and made 793ETH (~$2.7m), before closing all their socials, draining their crypto wallet, and shutting down the website. Since that moment, the URLs in the blockchain that pointed to the piece of art that the NFTs holder ‘owned’ just showed a 503 Service Unavailable message. All the users’ money was gone and, due to the nature of cryptocurrency, the money that was taken cannot be traced or returned.

Another major issue is insider trading or market manipulation. As many, many people purchase an NFT as an investment with the blind hope (or stated ‘promise’) that it will gain value, imagine this situation…

An end user sees a piece of art they want. Looking at the ledger in the blockchain, they see that it was originally sold for $300 and a day later re-sold for $900 and two days later $2000. This ‘asset’ has gained a 7-fold return so far. Talk about easy money! The end-user purchases this NFT for $3000 and waits for it to keep going up and up and up – and then it doesn’t. It turns out that the first, second, and third buyer were simply purchasing the NFT to inflate the price, whilst waiting for someone outside their friend circle to overbid so they could split the profit margin between themselves. It could even be one person with three different wallets buying the NFT from themselves each time to suggest the NFT is ‘hot’. This would be illegal ‘insider trading’ in the real world, but don’t imagine the governments of world are up to speed yet on how NFT markets work, because they’re not.

Also, when it comes to legislation, how would that ever work? Would the jurisdiction be with the nation the seller was from, the nation the buyer was from, where the owner of the website was from or what the locations of the servers was? It’s quasi-impossible to apply and, so far, governments don’t care enough. It’s simply not their problem.

NFT Marketplaces

If you’re concerned about the potential legitimacy of ‘closed shop’ markets as a buyer, you might want to direct your attention instead towards open markets. The most popular of these, right now, is OpenSea, which allows digital artists to upload their art and then ‘mint’ it as an NFT. End users can also sell on their art, as well as having a percentage of future sales, meaning they can earn again if a piece is resold, which is quite likely, given NFTs are being used more as investment items than keepsakes. As before, the artist retains ownership of the piece, as well as copyright.

The big difference here is to do with the process of minting, auctioning, bidding, selling and reselling, as recoding on the blockchain is a very computationally labour-intensive process and so comes with an array of fees. These fees might shock you, as they are fees you will have to pay in a marketplace scenario, unlike many company-owned NFT sites.

To explain this, we must first talk about the blockchain.

The Blockchain (an introduction) …

Without getting into too much detail, the blockchain, also known as a ledger, is a sequential record of events. The action of an event generates a unique hashcode and the next ‘block’ in the ‘chain’ contains this same generated hash, to confirm which block comes last. Therefore, if a block was maliciously inserted the hashes wouldn’t match, so should not be able to be validated. Also, with the hashcode being generated from the action of an event, if this action information was changed, the hash itself would change as well, which would also mean it wouldn’t be validated.

The blockchain is a decentralised system, meaning there are many, many copies of this ledger on many thousands of computers. Hacking or corrupting the blockchain is all but impossible. If one copy of the blockchain was hacked on one computer, most other computers would conclude the information was wrong and discount it. For a transaction to be confirmed, a simple majority (51%) of computers processing the blockchain need to agree.

As you might imagine, the process of validating across all these computers takes up a lot of power – and therefore electricity. Within the Ethereum blockchain, for example, actions can be anything from a record lookup to the purchase of an NFT, or even a piece of code someone might run. Due to this, Ethereum is considered a ‘Turing complete’ system (Google it!). Again, without getting too technical, something that is considered Turing complete suffers from ‘the halt problem’, meaning the problem is mathematically & programmatically IMPOSSIBLE to resolve – ie a piece of code that will stop (halt) or get stuck in an infinite loop.

If something were to get stuck in a loop, this would prevent the blockchain from adding more blocks, as the current block can’t end to produce the hash that’s needed for the next block, meaning the whole system falls down. To avoid this, as well as cover the costs of computational power and electricity, each transaction in the blockchain requires ‘GAS’. A user needs to purchase GAS to run something in this blockchain. For Ethereum, these are sold in units known as GWEI. One Ether coin is 1 billion GWEI. If we take an approximate value for ETH being ~$2800, one GWEI is 0.0002 cents in real money.

This GAS has a price per a unit (at this moment in time, it’s 70GWEI per unit of GAS), and, just like the cost of petrol, that price can go up and down, based on network demand. Some common functions performed on the blockchain have defined units that are required to carry out that task. There is also an overall GAS limit with the maximum you can use per block being 12.5 million GAS – and it’s this that stops the ‘halting problem’. If you run out of GAS, the block is reverted and the chain carries on. The user also doesn’t get their GAS money back, so it’s best to not submit forever looping requests.

As a point of reference, an NFT transaction takes a minimum of 21000 GAS units, so this needs to be purchased at the current spot price. There’s also an option to have your request processed quicker – imagine super-unleaded over unleaded petrol. At this moment the gas price is 71 GWEI, up 1 GWEI from a couple of minutes ago (it’s been from 50 – 140 today). Therefore, this transaction now would need 21000*71 = ~1.5M GWEI = 0.0015 ETH = $4.33

This is just one the many costs people might encounter. Let’s look at some others…

Selling art in a marketplace

On the surface, this process is marketing via a super-easy process. You join a site like OpenSea, open an account, create a collection, create your pieces and upload a JPEG of all your pieces. Someone offers 0.05ETH (as all NFTs are purchased using cryptocurrency, and almost exclusively Ethereum). This is currently around $145; boom happy times… However, there are fees, many fees, many expensive fees….

Firstly, the one-time fees. There is the initialisation fee to set up your account. This, like many, fluctuates based on the GAS fee, but could be around $150. If you want to use the auction feature within OpenSea you’ll need to pay an auction approval fee and you’ll also need to convert your ETH to WETH (Wrapped ETH), the currency that is used for auctions. This is also a GAS price defined cost.

Secondly there are the per item costs. There is an auction acceptance fee – also a GAS price defined cost. Also, since you will have to be paid in WETH, you’ll have to pay another GAS fee to convert this back in the ETH – and another GAS fee still if you want to convert it to more classical money.

Each of these steps can cost $10-$200 each, depending on the speed, whether lazy or on-chain minting (with lazy minting referencing something minted on the blockchain, which is cheaper, whilst on-chain minting shows the actual minting on the chain, the more expensive option) – plus OpenSea will take a 2.5% cut on any profit. Together with the Initialisation fee ($150), Auction Approval fee, ETH to WETH fee, Auction Acceptance fee, WETH to ETH fee, you would, for your first sale, have spent $190 – $550 in fees, for the sale of an item for $145; potentially making a loss. As a result, there is generally a floor or reserve price on auctioned items.

Fixed priced items carry fewer fees for the seller, as neither the approval for auctions nor the conversion of WETH to ETH (and back) are required. The seller also doesn’t pay GAS fees when an item is sold. You only pay if you cancel a listing, as it needs to be removed from the blockchain, so the sale can’t be completed. Instead, the seller pays these fees. For buyers this put extra burden on them, sometimes paying more in the GAS fees than the cost of the NFT itself.

An even more annoying situation for buyers, when paying fixed price, is if the collection is in high demand. Imagine a collection of 1000 items, and 1500 people select to purchase one of this collection when the sale starts. All 1500 will pay the GAS fees to process the transaction, but only 1000 with receive their NFT. Meanwhile, the GAS fee will not be refunded to those unlucky 500. Again, this is totally unregulated market and it’s simply rotten luck.

At this point you might be thinking that the people really making money are the processors of blockchain, taking a margin from the GAS fees to process your requests. You’d be right of course. In a gambling sense, as NFTs are basically an investment, this is like a casino taking a rake during a poker game. They never lose money – that’s for the punters to do.

Is a marketplace a safer environment to buy / sell NFTs?

I think it’s fair to say that a large company like OpenSea is unlikely to just fall off the face of the internet anytime soon, but if they did, all the NFTs (records in a database) would be worthless, and all your investment money would be gone. It’s true that any administration company can give you your asset back. However, this would just be a CSV of a data table, as this is all you effectively purchased.

Quite a few existing artists have recoiled in horror over the idea that many markets like this are duping people out of their money and giving them nothing other than a URL that points to a JPEG file that they can tell people they own – according to one website. Other artists have had their art stolen from their own websites and put up online as NFTs by a random stranger, ensuring they will never see any of the sale or resale money. Even a giant like Marvel had loads of tightly-controlled characters taken from their website and uploaded as NFTs. You might think this was clearly illegal but even this isn’t as simple as you might expect. As an NFT only represents the database row plus associated picture, as confirmed on the blockchain, the seller didn’t offer any image rights or copyright in the first place, so ‘selling’ these images wasn’t effectively promising anything that would infringe on Marvel’s legal copyright.

One artist described the NFT worth as an ‘ecological nightmare pyramid scheme’ (more on the ecological impact of NFTs later), whilst one gallery pulled out of setting up their own NFT market after only a few hours, due to tweets from artists like this:

Markets like that are also known as bubbles, and bubbles eventually burst.

Anton’s closing post on NFTs will be pusblished soon, where he asks: NFTs: What’s the point and why all the hype?